Changes in grain production across the DPRK were divided into three periods, i.e., continuous growth, violent fluctuation, and slow recovery. The data showed that grain production within the DPRK more than doubled from 4 million tons to 9.835 million tons over the period between 1961 and 1991.

It is clear that the period between 1992 and 1997 was characterized by violent fluctuations in grain production. This value dropped sharply from a peak of 3.35 million tons (1996) to a value even lower than that seen in 1961. A slow recovery between 1998 and 2019 meant that DPRK grain production gradually increased to the 1975 level, that was 6 million tons.

The staple grain crop in the DPRK comprises rice and maize. Rice is the main component of grain production, providing at least 43% of grain supply, and maize is the second major constituent. The proportion of maize out in the total grain production decreased significantly throughout the 1990s, while wheat production across the DPRK remained low. Beans production nationally remained relatively stable, while potato has been an important staple for the DPRK since the 1990s. A high potato yield could effectively alleviate grain shortages.

[…]

The United Nations FAO believes that it is safe for a country to reach 400 kg per capita of grain possession [38]. In this context, and according to the DPRK grain supply and consumption situation, this relationship transitioned from a ‘supply and consumption balance’ to a ‘supply exceeding consumption’ situation between 1961 and 2019 (Figure 4). This transition can be divided into two stages encompassing food and clothing (between 1961 and 1994) and poverty (between 1995 and 2019).

Thus, between 1961 and 1994, the DPRK actually achieved grain self-sufficiency and reached a basic balance between supply and consumption. Data show that per capita grain possession was basically maintained over this period at about 400 kg and that in some years it rose close to 490 kg.

Subsequent to 1995, however, grain production within the DPRK dropped sharply; considering imports and international assistance, per capita grain possession remained at about 260 kg around this time. It is noteworthy that since the implementation of international aid to the DPRK around 1995, more than 400,000 tons of grain was received each year. This equates to a cumulative total of more than 12 million tons.

However, as the DPRK population has grown rapidly, pressures on the grain supply have also greatly increased. Ensuring an adequate grain supply remains a major problem that will need to be solved in the future.

[…]

(1) It is clear that prior to 1992, the DPRK experienced a ‘golden period’ characterized by continuous improvements in grain production capacity [8–11]. The agricultural production levels throughout this period exceeded even those of China. Thus, the DPRK can solve the current grain problem by implementing an agricultural management system or a series of technological innovations [15].

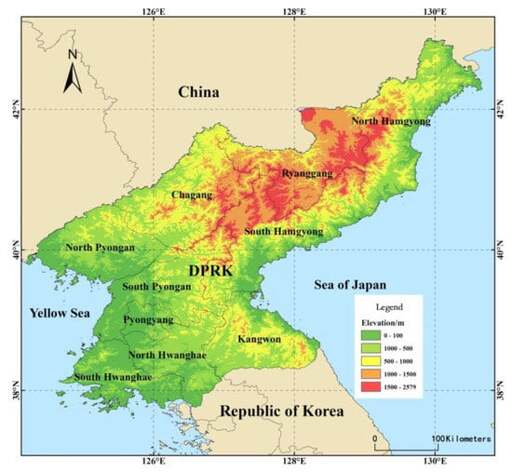

(2) The DPRK possesses favorable natural and water conservancy infrastructural conditions that can facilitate a substantial increase in its grain production capacity. As long as fertilizer production capacity and management levels are enhanced, the DPRK will maintain a significant potential to increase grain production [19].

(3) China and the DPRK are geographically close and related to each other historically. There is thus great potential to promote agricultural cooperation, especially in grain production, given the significant improvements on the Korean Peninsula since 2018.

(Emphasis added.)

The rest of the paper is a general analysis of the DPRK’s agriculture. You can tell that it’s maturely written since it does not toss around buzzwords such as ‘dictator’, ‘authoritarian’, ‘totalitarian’, or ‘hermit kingdom’ and the like; it also finds mundane reasons for the present difficulties in the DPRK’s agriculture, rather than either simply omitting the reasons or immediately blaming undefined phenomena like ‘collectivism’ or ‘communism’ (with the implication being that neoliberalism is the panacea). Overall, a worthwhile read, though it is a little technical.

A sobering remark from page 2:

no comprehensive multisource data analysis has so far been presented to assess grain supply and consumption within the DPRK.

(This was written in 2022.)

There’s a big overlap between communists and vegans, so yeah I’m really opposed to animal farming (it’s heavily industrialized)

If you think agriculture isn’t also heavily industrialized, I have a bridge to sell you.

Sure you can have some idyllic fields, but that wont feed many people.

Please re-read what I wrote. I said animal agriculture is bad. I didn’t say anything about plant agriculture. I’m ok with industrial plant ag but I hate animal ag