About two years ago I wanted to learn more about lichen. Since I cultivate mushrooms as hobby, I figured that attempting to isolate the wild lichen symbionts and then re-synthesizing the lichen would be a good way to learn about them. The experiment was not successful, in part because it is a long process and at one stage I did not give it the attention it needed. But at least I can share a bit of the process and observation.

Near where I live I can easily find Oakmoss (Evernia prunastri) and the Yellow Wall Lichen (Xanthoria parietina).

I collected small samples of each and placed very small pieces of them into many agar dishes. The idea here is that, coming from a wild source, contaminants will be present for sure. The process of isolation is an iterative process in which you observe the growth on the plate, pick out a small region where your target organism is growing strongly, and then move it into another plate.

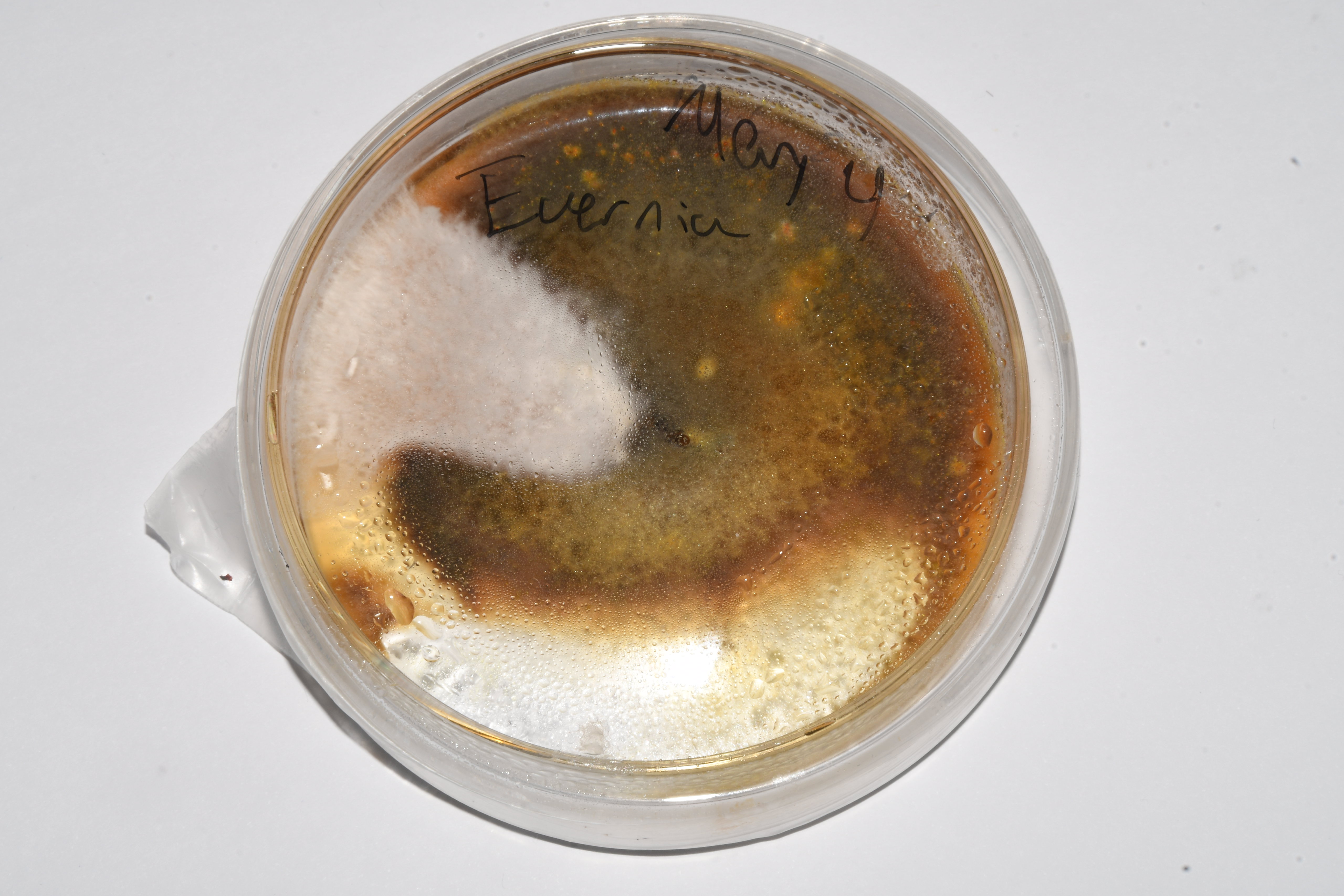

This is an agar plate into which pieces of Evernia were added:

In this image you can see that there is a wedge with fluffy white mycelium, which was consistent with the morphology for the mycelium of this species as described in the literature. So, I would pick a tiny piece from this region and transfer into a new plate, to obtain a clean mycelium after 1 or 2 transfers:

This process was also performed for Xanthoria parietina.

After this step, I had plates with “clean” mycelium but not yet confirmation that the mycelium was truly the lichen’s mycobiont. That is when microscopic identification comes into play. I was especially happy with the microscopic images I was able to get of the Xanthoria because they clearly show structures that are very characteristic structure of “septate, pluricellular, branched hyphae” described in the literature.

At this point I now had the fungal component isolated in agar plates. This was for me the easy part because I am familiar with growing mushrooms. But to build a lichen we need two parts: a fungus and an algae.

From a search I could find that both lichen species may use algae of the genus Trebouxia as a symbiont. I placed small pieces of each lichen into water and made the following observations:

- When placed in water, some of the algal cells become dislodged and float away

Photo: Algal cells floating away from a piece of Evernia prunastri

- The algal cells can be seen held loosely in between the hyphae, rather than incorporated into the hyphal structure

Photo: Algal cells loosely bound to the hyphae of Evernia prunastri

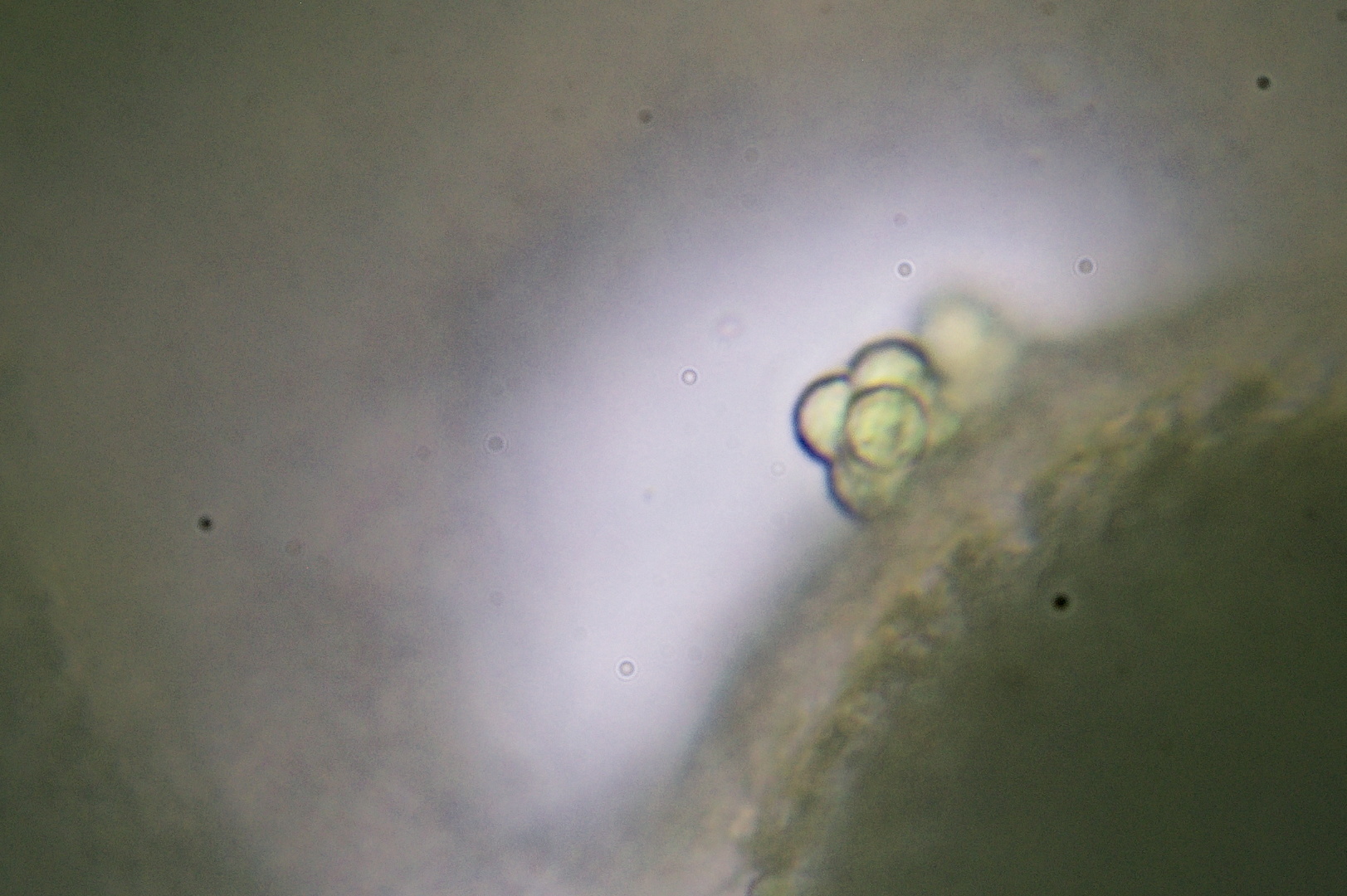

Photo: Cluster of algal cells bound to the surface of a hypha of Xanthoria parietina

- Both species contained algar with similar if not identical round morphologies

Photo: Individual algal cell released from Xanthoria parietina

- The round morphology is consistent with Trebouxia

… So, at this point I had successfully isolated the fungal partner and had some evidence to suggest that the binding between the fungus and the algae is loose. Since I saw that the algae could be released from a lichen, an easy thing try was to attempt to transfer the algae from a living lichen to the mycelium culture.

This is a photo of that attempt. Small pieces of wild Evernia were placed on top of a mycelium culture that was already several weeks old.

This… Did not work at all. The culture eventually became contaminated and was thrown away.

The next attempt was to try to grow the algae separately. One method was to place the wild lichen into agar dishes with no added nutrients end expose the dishes to the sun. The logic here is that the algae will survive from photosynthesis while the rest of the species do not have the nutrients to thrive on. I tried this on about 15 plates, different light conditions, but nothing grew other than a few weakly growing contaminants in some of the dishes…

Another method was to place the lichen into a glass jars filled with water and place those by the window at different levels of shade.

In the meantime, I decided to grow “grain spawn” jars out of the mycobiont thinking that this would give me a lot of material to work with once the algae grew. Both fungi did colonize the grain well. However, those jars were abandoned and eventually, after several months of storage, became contaminated and I had to toss them away.

It has been almost two years and I just had a look now at how the algae in jars are doing.

In the Xanthoria jar I can see significant algal growth. As for the Evernia, the algae did not make it but it looks like the mycelium did, as it has created a floating white blob.

A few months after having the algae jar sitting by the window I analyzed the mixture under the microscope and did observe a large amount of Trebouxia.

Right now I have checked another sample, and, while I do see what looks like a bit of Trebouxia (marked with a red arrow), unfortunately most of the mixture now consists of other unidentified algal species. Since Trebouxia is not the dominant species, it would probably be easier to re-isolate the algae from the wild instead of trying to isolate it from this mixture.

I will give it a second try, and this time I will place more emphasis on culturing the algae first and keeping the cultures healthy and pure.

This is awesome! Something I do when putting lichen under the scope is take a small section and smash it up against a stainless steel tray with the back of a scalpel handle, kind of like a mortar and pestle. I just do this because I’m lazy but it actually dislodges a decent amount of the algae from the hyphae. I wonder if you could then do something similar to spore isolation under the microscope with a capillary tube (I’ve never tried but here’s a video ). This is really cool and I’m so glad you shared this. There is a section in Lichen Biology by Thomas Nash on cultivating lichens in the lab.

That’s a good idea, I will give it a try. I also want to learn more about how to apply dyes to see the different structures.

I have been looking for good books on fungi and lichen. I have ordered that book, should arrive this week! Thank you for the recommendation

The spore isolation thing would definitely be a bit of a hassle, there’s probably a better way but it would be neat to see how it goes.

Its an excellent book, pretty easy to digest for the most part and answered a lot of my burning questions when I just could not find the answers online.

The book arrived :D Exciting!

I do want to try the single-spore isolation technique at some point.

Thanks for sharing this. I have very little understanding of any of this, but it was a facinating read. Please try again and report the results!

Thanks! Today I collected a tiny piece of the lichen and set up a new experiment to grow the algae!

The lichen organism consists of a combination of different species combining into one — a form of symbiosis. Generally, the lichen consists of at least one species of fungus, known as the mycobiont, and at least one photosynthetic alga or a cyanobacterium as a symbiotic partner, known as the photobiont. It is possible to have more complicated mixtures, not necessarily only two.

The fungus grows on a surface and then undergoes a process of lichenization. In this process, it can capture its companion from the environment (it may arrive via arthropod activity, such as through saliva or feces), and then produces structures within which they reside, as shown in the diagram below.

Source: New PhytologistThis relationship is beneficial to both organisms because the lichen can “mine” nutrients like phosphorus and also provide protection, while the photobiont can make use of light to produce sugars for the fungus.

It is difficult to cultivate these by picking one from the wild (except perhaps if you bring the lichen along with the surface it lives on), because this state of symbiosis is strongly adapted to the surface the lichen grows on and it has gone through a developmental history that is not easy to replicate from a small fragment.

One way to grow a few specific species of lichen is through a process of re-synthesis. This process consists of first growing the fungus and the algae separately, and then re-combining them to create the lichen.

Source: BMC GenomicsI still have not gotten to the point… but I have read about it and I think I now know how to do it. I need to make an agar plate like the ones I showed in the post that contains nutrients, but then place a thin regenerated cellulose or cellophane membrane on top of it that allows nutrients to flow slowly, but that the fungus is unable to penetrate, forcing it to only grow in a plane. After it has grown for a couple of days, the algae can be added in a specific ratio for the fungus to capture and become a lichen.

Hope this explanation helps clarify!

Here is also a very nice video on lichens: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0GOgiJlHkcY