No, I’m not putting this in /c/electoralism , for reasons found in the third paragraph

Most people know there’s first-past-the-post and there’s ranked-choice. But I’ve recently learned there’s a much longer list than that, and they all have pros and cons.

Somecomrades would say 🙄yeah bourgeois elections who cares🙄 but that is wrong: the mathematics applies to all voting. It’s the engineering side of the question: “If we have a bunch of people, maybe a hundred, maybe a million, how do we decide what the collective will is in the fairest way?” The name of the field is social choice theory because a social group is trying to make a choice.

You: oh bourgeois elections are a farce lol

Me: exactly and that’s why we need to study how can voting be not a farce

First-past-the-post gets a hard time, and deservedly so. But the people who say “first-past-the-post bad, ranked choice good” are oversimplifying. It turns out there are all these mathematical trade-offs, and it is formally provable that there is no perfect system.

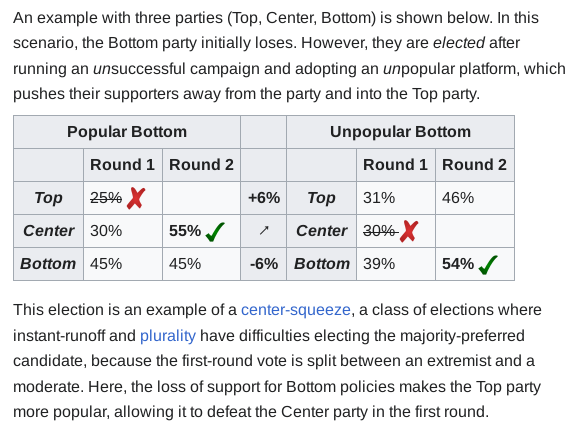

Most ranked choice voting systems* can suffer from a crazy effect where getting more votes makes you lose. The technical name for this is a monotonicity failure because mathematicians are shit with names. (*There are theoretical ranked-choice votings that don’t fail monotonicity, but I don’t know of any being applied in a political system. Companies probably have used them.)

In the ‘Popular Bottom’ Scenario,  gets 45% of the vote and isn’t elected; but in the other scenario he gets 39% and is elected. What happened is he lost supporters to a rival (Top) who eliminated his other rival (Center) for him, so he was able to sneak in.

gets 45% of the vote and isn’t elected; but in the other scenario he gets 39% and is elected. What happened is he lost supporters to a rival (Top) who eliminated his other rival (Center) for him, so he was able to sneak in.

First-past-the-post doesn’t have this problem: more votes is always better. But it has plenty of other problems. The USA system fails the no favorite betrayal criterion catastrophically; that’s the criterion that you should be able to vote for who you like best. Usans “have to” vote for a candidate they hate.

This page summarises it pretty well: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_voting_rules with tables comparing the different traps multi-winner systems fall into and the traps single-winner systems fall into.

Some cool systems:

-

PDF – “This paper discusses the protocol used for electing the Doge of Venice between 1268 and the end of the Republic in 1797”

Anyway, interesting stuff to think about if we design democratic/anarchistic systems for collective decision-making. It wouldn’t have to be electing representatives, it could be voting on policies, same maths either way.

Liberalism is “the ideology of capitalism,” of course, but also all the stated beliefs about individual freedom, one man one vote, self-determinism, everything that makes westerners feel warm and squishy. I believe all of this is ultimately based in idealism; in a fundamental belief that society progresses through the competition of ideas, and that the best ideas win out when they are explained to the masses. The search for the best voting system seems like the search for the final proof that society really can be improved one good idea at a time.

Rather than, you know, reckoning that the history of politics is the history of class struggle.

So starting with the assumption that people who want to build a hospital negotiated for the resources to be diverted to build exactly one hospital (in today’s world: they got a grant from the feds):

Voting obviously isn’t where we start; if each individual has a different idea of where to build the hospital there’s nothing to vote on.

Influential individuals might put forth ideas or arguments as to where to put the hospital, and they might collect others around them and organize for their preferred location. Maybe opinion coalesces around two locations, A and B. We now have two affinity groups, who have decided they have a collective interest in each of those locations, with people making any number of individual negotiations to land themselves in those groups.

The politics happened when people organized themselves into groups and decided on their interests. Ideally, the final decision would involve a negotiation between these groups (hospital goes to A, but with a tram line to the largest neighborhood near B, or whatever).

This isn’t really very different than how it works now, except now the groups wouldn’t usually have any public involvement since most people intuitively understand that they have no political relevance. Some capitalist who wants A will direct their lobby group to ask that of officeholders, maybe capitalist B also exists, maybe others if they don’t get scared off by the competition. The officeholders don’t generally have any personal interest in the outcome—they aren’t members of either group in our example—but they have interests in keeping various lobby groups happy and might negotiate with them on those terms. The point is that the political negotiations always happen.

The final voting on A or B, if it happens, is just a formality. Even if we had direct democracy the process to get to those two was much more impactful, and only the really interested would come out to vote anyway, making it again mostly a formality. If you could force every person to have an informed opinion on A or B, and then force them all to vote, then certainly the result would be meaningful… but this comes back to exactly my point about idealism.

Ultimately my point here is that matters of public political opinion only exist in the kind of mathematical models used to evaluate different voting systems. All real politics is negotiation, and finding the best voting system is irrelevant.